It seems that all I needed to align my thoughts and find some inspiration was a motorcycle accident. Who knew that a sudden meeting with the pavement was the secret to unlocking writer’s block? Now that I am back in one piece and feeling strangely inspired, let’s talk about something almost as painful as crashing: Java Concurrency.

I have spent the last few years building cloud native applications on OCI. The transition from legacy monoliths to containerized microservices usually brings a promise of unlimited scalability. However, it also brings a new set of problems that only appear when you are operating at scale.

Recently I faced a classic backend challenge. I had a scheduled job that needed to process a massive dataset. It had to wake up, iterate through ten different geographical regions, fetch thousands of orders, and then make individual gRPC calls to enrich the product data. We are talking about handling a throughput of hundreds of thousands of requests per second.

My first instinct was the same one many engineers have. I have a machine with 8 cores in the Oracle Kubernetes Engine, so I should use all of them. I decided to parallelize everything.

That decision started a chain reaction that taught me more about the JVM memory model than any textbook ever could.

The parallelStream() Trap

My initial approach was the naive use of the Java Stream API. I simply changed my sequential streams to parallel streams. It felt like a free performance boost.

The problem arises when you nest parallel streams like processing regions in parallel while simultaneously processing orders in parallel inside those tasks. You are not actually multiplying your processing power. You are just saturating the Common ForkJoinPool.

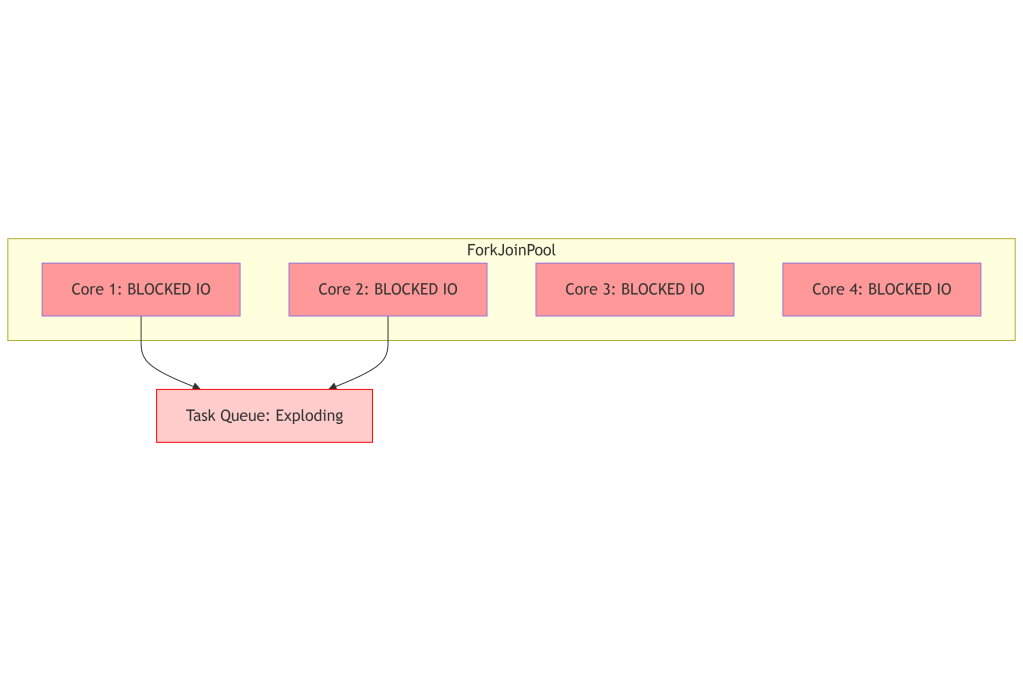

The Common ForkJoinPool is a static thread pool shared across the entire JVM. By default, it has a size equal to the number of your CPU cores minus one. When you nest parallel streams, the inner tasks and outer tasks compete for the same limited worker threads.

In CPU-bound scenarios such as mathematical calculations, this approach works fine. But my workload was IO-bound. My threads were not calculating digits of Pi. They were waiting for network packets from a gRPC service.

This led to a state of thread starvation.

The worker threads were blocked waiting for IO, while the task queue kept growing. The CPU spent more time context switching between blocked tasks than actually doing work. The result was unpredictable latency and a system that crawled.

The Illusion of CompletableFuture and OOM

I realized that blocking threads was the enemy. I decided to refactor the code to be asynchronous using CompletableFuture and a custom ExecutorService. The theory is sound. You trigger a request and release the thread back to the pool while the operating system handles the network wait.

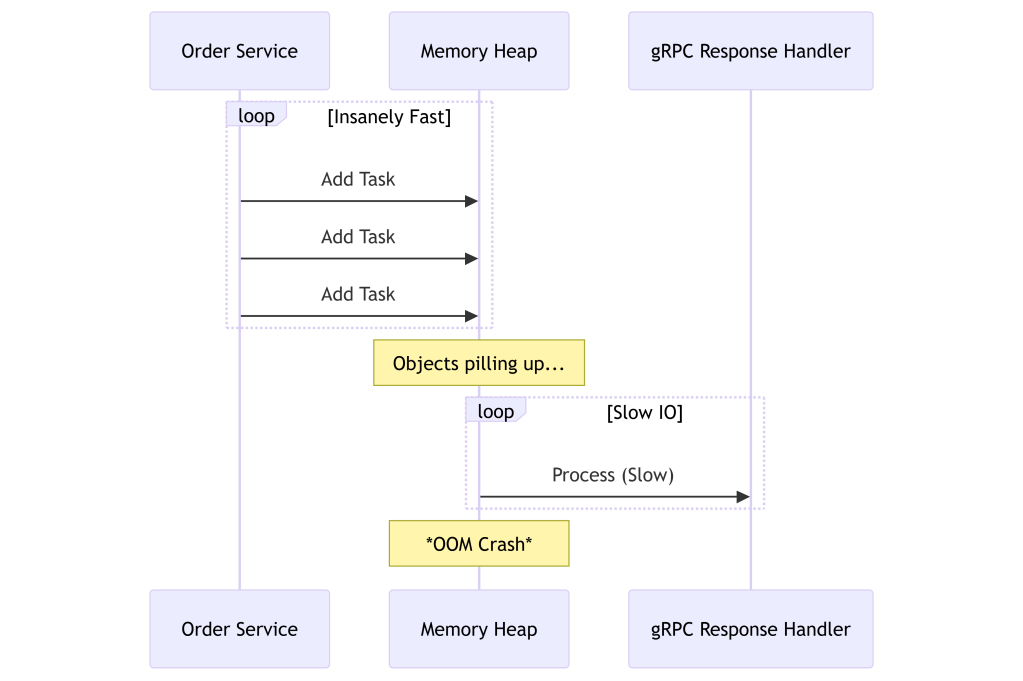

The code became non-blocking and indeed it was incredibly fast. It was too fast.

I immediately encountered a java.lang.OutOfMemoryError.

The root cause was a lack of backpressure. My service acted as a producer that generated requests infinitely faster than the downstream gRPC service could respond. I was queuing millions of response handling tasks into the heap memory.

The heap filled up with pending CompletableFuture objects. I was essentially launching a DDoS attack on my own application. This taught me that speed without control is just a faster way to crash the application.

Virtual Threads: The Promise vs The Reality

Then I looked at Java 21 and Virtual Threads. This feature promises lightweight threads managed by the JVM rather than the OS. You can theoretically create millions of them without the memory overhead of platform threads.

I implemented a newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor hoping it would solve my resource management issues.

It did not. I hit two major roadblocks.

First was the Pinning issue. In Java 21, if your code executes inside a synchronized block, the virtual thread gets pinned to the carrier platform thread. This effectively turns your fancy virtual thread into a heavy blocking thread. This happens deep inside some third-party libraries and is hard to debug without specific JVM flags.

The second issue was resource exhaustion. Virtual threads are cheap to create. However, the resources they connect to are expensive.

You can create 100,000 virtual threads easily. But you cannot open 100,000 database connections or 100,000 open file descriptors. My application tried to open more network sockets than the OCI Linux node allowed, causing the application to crash again.

The Solution: Back to Simplicity

The answer was not more advanced features but simple control mechanisms. I needed to decouple the submission of tasks from the execution of tasks.

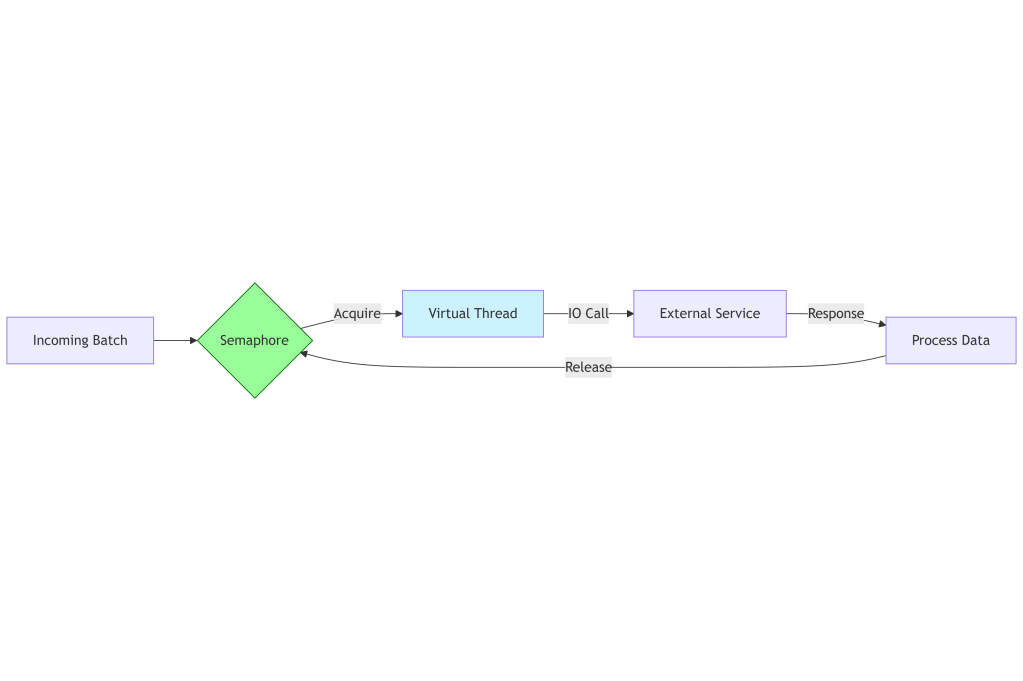

I implemented a Semaphore to act as a gatekeeper.

I went back to a design where I explicitly control concurrency. It does not matter if I use Virtual Threads or Platform Threads. I need to limit the number of in-flight requests to a number that my infrastructure and the downstream service can handle.

The final architecture that is now running in production on OKE looks like this:

I simplified the code significantly. I removed the nested parallel streams that caused the contention. I removed the complex chains of futures that made debugging impossible.

I used Virtual Threads for their readability benefits. They allow me to write code that looks sequential but behaves asynchronously. However, I wrapped the execution in a Semaphore with 50 permits.

Final Thoughts

In engineering, we often confuse performance with maximum throughput. But in cloud native systems, real performance is stability under load.

My job is not to make the code go as fast as possible in an ideal scenario. My job is to ensure the code does not commit suicide when traffic spikes.

Sometimes the mature technical decision is forcing your code to slow down. It is setting a hard limit. It is accepting that even though you can open a million threads, you should only open fifty.

And in that control is where real engineering lives.

Leave a comment